One of the gifts of the Revised Common Lectionary (RCL) is the opportunity to appreciate each Gospel as a distinct jewel in the library of the New Testament. The Gospels are not just four collections of the words and actions of Jesus, from which we might cut and paste our own version of his biography, they are complete books with their own shape and style. We need to treasure each one and give it our close attention if we are to get the best from it.

In Year A of the RCL, we are in the year of Matthew. How can we best pay attention to Matthew’s Gospel? How can we access this writer ‘Matthew’ as a teacher, mentor and guide, our companion on our journey of faith? How can we develop some insights emerging from the text that will nourish us and, in turn, help us to feed others?

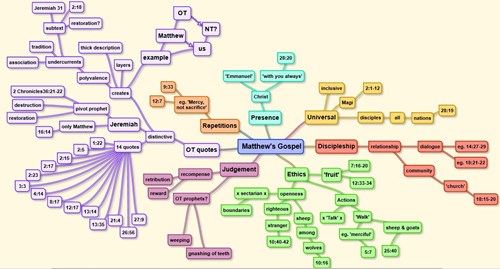

I would encourage you to immerse yourself in the text and allow it to both delight and perplex you, and to set you a series of questions rather than to provide you with cut and dried answers. Aim less for perspective as a reader (that keeps the text at a distance) and more for immersion (that allows the text to affect you and change you). Ask the question, important in all Bible Study, ‘What’s in it for me?’ In other words: What here speaks to me, challenges me, models to me a different way to live? For instance, it is often observed that Matthew is the Gospel with the strongest links to Judaism; this is a safe assertion considering the fourteen quotations and allusions to the Old Testament, eleven of which are unique to Matthew’s account (the references are listed on the mindmap branching from ‘OT Quotes’). But the question remains, ‘What’s in it for me?’ Where might this observation lead?

Matthew and the Old Testament

One effect of quoting verses from the Old Testament is that it allows Matthew to tell a multi-layered story: there is the detail about the life of Jesus (e.g. Herod slaughtering the boys in Bethlehem), and there is another level of story that he draws in from Jeremiah 31. The full chapter in Jeremiah is about restoration – so perhaps Matthew is bringing in an undercurrent of hope? The anguish and loss is desperate – here are the tears of Rachel weeping for her children – and nothing can lessen this. Nevertheless, there is another level to the story, containing hope and purpose. Matthew keeps these two levels working together – the hope does not eclipse the pain, and vice versa. Perhaps we can be Matthew’s apprentices and learn to do this two-level interpretation with the text of his Gospel and the detail of our own lives? Perhaps this is a way not to be simplistic, and yet to be full of hope. Another use Matthew makes of the Old Testament is to give the same quotation in two different incidents, e.g. the phrase ‘I desire mercy, not sacrifice’ – see Repetition on the chart below. This suggests that Matthew cites the Old Testament to open up the meaning of his story, rather than to tie it down to one single idea. How willing are we to explore extra (or even alternative) meanings for a saying or an event?

Mercy and judgement

Although Matthew has powerful things to say about mercy, his Gospel is not known for this theme. He is famous for the phrase ‘weeping and gnashing of teeth’ and for ferocious sayings about judgement (e.g. 8.12; 22.13; 25.30). There is no explanation for these sayings that will remove their sting. We need to note our discomfort and work with it, especially as the recipients of these sayings were not ‘tax collectors and sinners’ (9.10-13) but religious people, both Pharisees (23.27) and Christians (7.21-23). The theme of judgement places Matthew in the same family tree as the Old Testament prophets, and he shows that they share common DNA when he speaks of retribution and reward. Judgement But these warnings and condemnations do not stand alone, they come in the midst of Matthew’s focus on ethics – on the ‘fruit’ in people’s lives, on the actions and results that come from their beliefs, on avoiding the hypocrisy of saying one thing and doing another. His motto could be: ‘Love is as love does’. Ethics. There is a tremendous openness here: if we understand the true nature of someone by what they do, then it does not matter what religious label they have: 'Blessed are the merciful, for they will receive mercy' (whether or not they subscribe to my creed). Matthew’s faith is not at all clubbable – he looks out on the world to see signs of the kingdom. Universal.

Matthew's church

This looking outwards proceeds from strong relationships and a significant community. Matthew’s Gospel uses the word ‘church’ for a community of Christians, for instance. He also uses direct speech when Jesus meets people Discipleship – there are questions and answers, and the point of a story emerges through dialogue and encounter. However tough and demanding the road, this Gospel never requires us to travel alone. Presence It is Matthew who tells us that Jesus is called ‘Emmanuel’ (God is with us), and this is the only Gospel to end with Jesus speaking: ‘And remember, I am with you always, to the end of the age.’

Click on the image to see a PDF.

The Revd Dr Rachel Nicholls, an Anglican Priest in the Diocese of Ely, also works as a creative writer and graphic designer.